Jobs

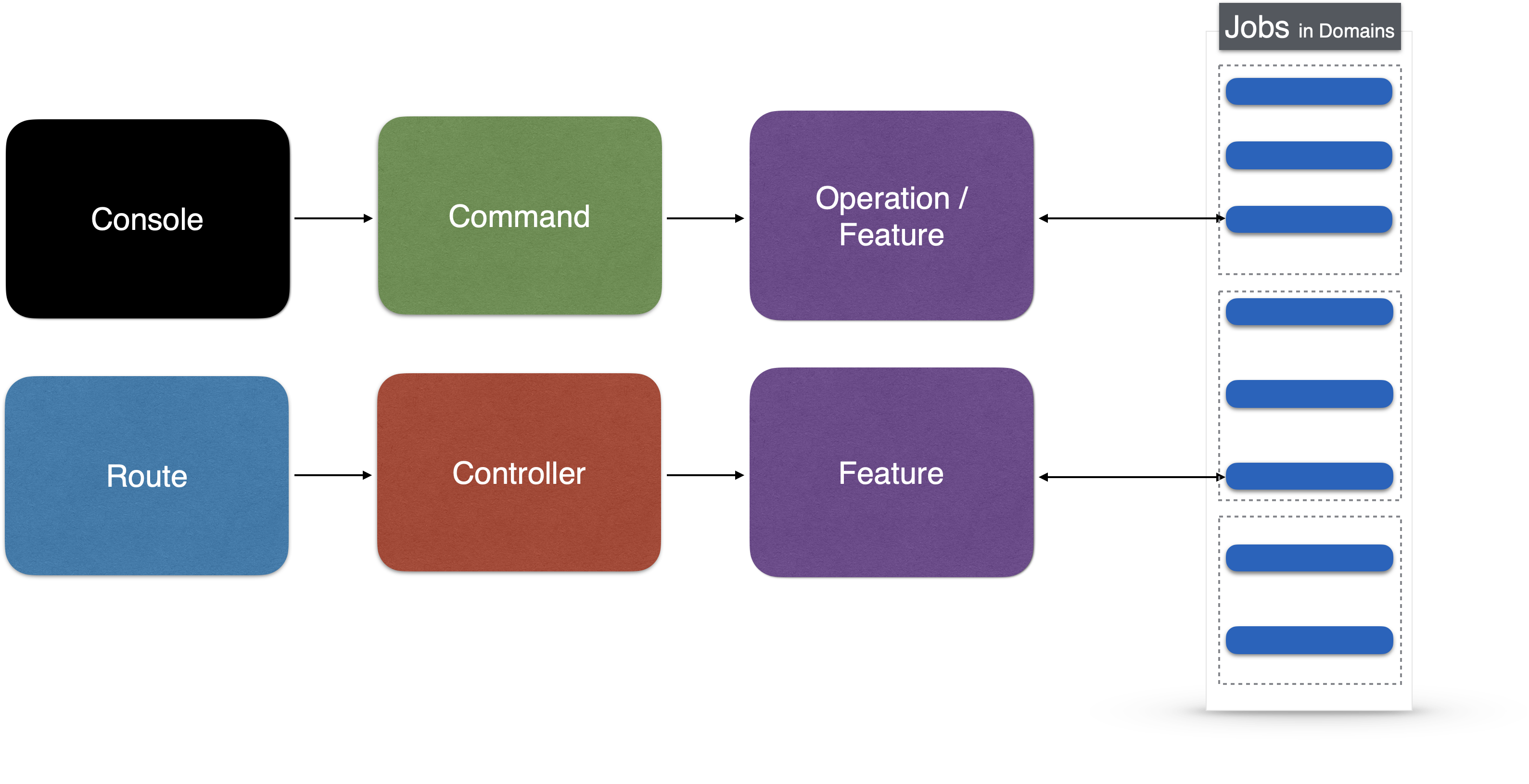

Jobs do the actual work by implementing the business logic. Being the smallest unit in Lucid, a Job should do one thing, and one thing only - that is: perform a single task. They are the snippets of code we wish we had sometimes, and are pluggable to use anywhere in our application.

Our objective with Jobs is to limit the scope of a single functionality so that we know where to look when finding it, and when we’re within its context we don’t tangle responsibility with other jobs to achieve the ultimate form of single responsibility principle.

Usually called by a Feature or an Operation, but can be called from anywhere by any other class once setup as a custom dispatcher; hence, being the most shareable pieces of code.

Jobs in Domains

Domains are where jobs live. It is how they’re organized in the folder structure, and represent the execution point of a single functionality within the corresponding domain. In other words, the only way to access a domain should be through a Job.

Here’s an example of two domains (User & Product) exposing functionality through jobs.

- User [domain]

LoginUserJobLogoutUserJobUpdateUserProfileJob

- Product [domain]

FindProductByIDJobSearchForProductJobSaveProductDetailsJobValidateProductDetailsJob

Each of these is a class. Similar to other Lucid units it uses __constructor to define required parameters and is executed

through the handle method when calling run.

Example

In a Feature or Operation we can use $this->run(ValidateProductDetailsJob::class) or $this->run(new ValidateProductDetailsJob()) to run the job’s handle method.

app/Domains/Product/ValidateProductDetailsJob

use Lucid\Units\Job;

use App\Domains\Product\ProductValidator;

class ValidateProductDetailsJob extends Job

{

private array $input;

public function __constructor(array $input)

{

$this->input = $input;

}

/**

* @param ProductValidator $validator

*

* @throws InvalidInputException

*/

public function handle(ProductValidator $validator)

{

$validator->validate($this->input);

}

}

And in our feature: .../Features/AddProductFeature.php

use App\Domains\Http\Jobs\RespondWithJsonJob;

use App\Domains\Product\Jobs\SaveProductDetailsJob;

use App\Domains\Product\Jobs\ValidateProductDetailsJob;

class AddProductFeature extends Feature

{

public function handle(Request $request)

{

$this->run(new ValidateProductDetailsJob(

input: $request->input(),

));

$product = $this->run(new SaveProductDetailsJob(

title: $request->input('title'),

price: $request->input('price'),

description: $request->input('description'),

));

return $this->run(new RespondWithJsonJob($product));

}

}

Characteristics

- Unlike other units (feature & operation), jobs don’t call other jobs to avoid obscure nested logic that end up being hard to follow and maintain.

- Jobs do not know about other units, they operate in isolation and are unaware of their surroundings. If they were people, they would’ve been called selfish for only being concerned with themselves and their needs to perform their task.

- Constructor parameters of a job - a.k.a. job signature - should be about the job itself only, not concerned with where it will be called from and in which conditions. Here’s a personification of a Job speaking:

I, as a Job, in order to fulfill my task, I need “X” and “Y”, and once I am done I will return “Z” to you.

To validate your choice with jobs, simply ask yourself: “what does this job do?” and the answer should be “It [does this] then returns [that]” where:

- [does this]: should not include an “and” and should be made up of few words (single responsibility)

- [that]: ideally should either be an object, or a status response (boolean).

TIP: Avoid returning associative arrays as much as possible, or at all if possible. They ramp up undefined structures and it will require more cognitive load over time to figure out their structures and values.

It is common practice to share jobs, in fact they are the units that are shared the most in code. For that reason we strive to make their code cover the entire spectrum of the task they perform, while careful not to end up having complex jobs just for the sake of reusing them.

Good balance between complexity and functionality is key with jobs, it gets better with time and the more you familiarize yourself with Lucid!

Generate Job Class

Use lucid CLI to generate a Job class that extends Lucid’s Job base class by default, which handle method is invoked when run by an Operation, Feature or a custom dispatcher.

Signature lucid make:job <job> <domain> {--Q|queue}

Example

lucid make:job FindProduct product

Generated class will be at app/Domains/Product/Jobs/FindProductJob.php

and its test at tests/Unit/Domains/Product/Jobs/FindProductJobTest.php

Signature lucid make:job <job> <domain> {--Q|queue}

Example

lucid make:job FindProduct product

Generated class will be at app/Domains/Product/Jobs/FindProductJob.php

and its test at tests/Unit/Domains/Product/Jobs/FindProductJobTest.php

The generated Job class will automatically be suffixed with Job, so there’s no need for it to be specified in the command.

For more details on this command see the help manual with lucid make:job --help

Calling Jobs

Jobs are called using the run method that’s provided by extending one of Lucid’s runner units Feature & Operation classes,

which internally relies on UnitDispatcher trait.

Signature

run($job, $arguments = [], $extra = [])

$jobcan be either aJobinstance or the job’s class name (usually usingSomeJob::class)[$arguments]is the associative array of arguments mapping the Job’s constructor parameters. Only used when$jobis the class name and not the instance.- [

$extra] is for the Laravel dispatcher and is not used by Lucid for any purposes, passed straight to the dispatcher.

Dispatching Jobs & Arguments

Given this sample job that updates a product’s info in the database:

namespace App\Domains\Product\Jobs;

class UpdateProductDetailsJob extends Job

{

public function __construct(int $id, string $title, string $price, string $description)

{

$this->id = $id

$this->title = $title

$this->price = $price

$this->description = $description

}

public function handle(): bool

{

$product = Product::find($this->id);

$product->fill([

'title' => $this->title,

'price' => $this->price,

'description' => $this->description,

]);

return $product->save();

}

}

Calling this job from a feature or an operation is straight forward using run():

$this->run(new UpdateProductDetailsJob(

id: $request->input('id'),

title: $request->input('title'),

price: $request->input('price'),

description: $request->input('description'),

));

$arguments are sent as an associative array where the key should match parameters’ names exactly, but not their order.

Meaning that we could tangle parameter order, reducing the amount of change required when updating the job with new order of arguments

or additional optional ones.

This would still work:

$this->run(new UpdateProductDetailsJob(

title: $request->input('title'),

description: $request->input('description'),

price: $request->input('price'),

id: $request->input('id'),

));

Also, aesthetically allows to organize parameters by length which is nicer to look at!

This is the recommended way of calling jobs, for it makes reading run statements in features and operations explicit and requires a reduced amount of knowledge, which preserves mental space for what actually matters.

Dispatching Job Instances

Given this simple job that retrieves a user from the DB by their identifier:

namespace App\Domains\User\Jobs;

class GetUserJobID extends Job

{

private int $id;

public function __construct(int $id)

{

$this->id = $id;

}

public function handle()

{

return User::find($this->id);

}

}

We can simply initialize an instance and run it:

$this->run(new GetUserByIDJob($userId));

and it works exactly the same as if we did run(GetUserByIDJob::class, ['id' => $userId]).

$arguments won’t apply when an initialized job is run.

Since the job requires only one argument, and looking at the run line is intuitively indicative of the intended functionality

and the argument, we can simply initialize the job ourselves and pass it to the dispatcher.

This is familiar with jobs that are known to (almost) never need to evolve beyond their initial functionality, and is surely not recommended when the job requires two or more parameters because of the extra effort required to figure out the parameters when reading run statements.

Take for example the case of a job with more parameters:

$this->run(new UpdateProductDetailsJob($id, $title, $description, $price))

instead of this:

$this->run(new UpdateProductDetailsJob(

id: $id,

price: $price,

title: $title,

description: $description,

));

Choosing Between Initialization & Separate Arguments

As mentioned above, it is recommended to always use named parameters for it makes code easier to read when there are multiple jobs in a sequence.

Here’s a comparison of the two approaches in the following handle method, could be for a feature or an operation:

Separate: A bit more writing but clearer when reading.

public function handle(Request $request)

{

$this->run(new ValidateProductInputJob(

input: $request->input(),

));

$photos = $this->run(new UploadProductPicturesJob(

cover: $request->input('pictures.cover'),

showcase: $request->input('pictures.showcase'),

));

$product = $this->run(new CreateProductJob(

title: $request->input('title'),

price: $request->input('price'),

description: $request->input('description'),

provider: $request->input('provider'),

photos: $photos

));

$isStockUpdated = $this->run(new UpdateProductStockAvailabilityJob(

id: $product->id,

availableCount: $request->input('available_count'),

));

return $this->run(new RespondWithViewJob(

data: $product,

template: 'product.update',

));

}

Initialized: Fast to write but harder to read.

public function handle(Request $request)

{

$this->run(new ValidateProductInputJob($request->input));

$photos = $this->run(new UploadProductPicturesJob(

$request->input('pictures.cover'),

$request->input('pictures.showcase'))

);

$product = $this->run(new CreateProductJob(

$request->input('title'),

$request->input('price'),

$request->input('description'),

$request->input('provider'),

$photos)

);

$isStockUpdated = $this->run(new UpdateProductStockAvailabilityJob(

$product->id,

$request->input('available_count'));

}

Queuable Jobs

You may turn any job into a queueable job that will be dispatched using Laravel Queues rather than running synchronously,

by simply implementing ShouldQueue interface.

Generate Queueable Job

lucid make:job UploadPhotos files --queue

Will produce the following job class:

class UploadPhotosJob extends Job implements ShouldQueue

{

public function handle()

{

// photo uploads will be processed in the queue

}

}

This job will be treated exactly as Laravel treats queued jobs.

Specify Queue Name

public function __construct()

{

/*

* set the name of the queue on which to dispatch this job.

* if using Horizon, this should be the same as the one configured there.

*/

$this->onQueue('emails');

}

Custom Dispatcher

You may turn any class in your application into a job dispatcher.

To equip a class for running jobs use Lucid\Bus\UnitDispatcher trait.

use Lucid\Bus\UnitDispatcher;

class Handler extends ExceptionHandler

{

use UnitDispatcher;

public function custom()

{

return $this->run(new TheJob());

}

}

Handling Errors with Jobs

It is common to want to dispatch jobs from Exceptions\Handler,

where you may want to centralize your error responses in jobs to maintain a consistent structure across your application.

Assuming that we are working on an API where all our errors must be returned in JSON format, to avoid the accidental rendering

of an HTML page leading to unexpected behaviours. We would create a job to be run when encountering an exception that includes

the response structure. Lucid ships with one that can be used as default, available in the built-in Http domain App\Domains\Http\Jobs\RespondWithJsonErrorJob which has a simple signature:

$this->run(new RespondWithJsonErrorJob(

options: 0, // will be passed to ResponseFactory::json()

code: 2900, // custom error code, optional, default: 400

status: 400, // HTTP response status code, optional, default: 400

headers: [], // customize headers

message: $e->getMessage(),

));

Running this job in response to our exceptions will guarantee that the consumer always receives a consistent JSON structure:

{

"status": 400,

"error": {

"code": 2900,

"message": "Expressive message about the error."

}

}

Rendering Exceptions

In our Handler class we can register a custom rendering Closure for exceptions of a given type and use the job to render JSON.

use App\Exceptions\CustomException;

/**

* Register the exception handling callbacks for the application.

*

* @return void

*/

public function register()

{

$this->renderable(function (CustomException $e, $request) {

return $this->run(new RespondWithJsonErrorJob(

status: 500,

message: $e->getMessage(),

));

});

}

You may also wish to return a view in the case of an HTML response instead:

use App\Exceptions\CustomException;

/**

* Register the exception handling callbacks for the application.

*

* @return void

*/

public function register()

{

$this->renderable(function (CustomException $e, $request) {

return $this->run(new RespondWithViewJob(

status: 500,

template: 'errors.custom',

));

});

}

Reportable & Renderable Exceptions

Similar to our Handler class, we may have our exceptions render themselves by defining render method in the exception class.

namespace App\Exceptions;

use Exception;

use Lucid\Bus\UnitDispatcher;

class RenderException extends Exception

{

use UnitDispatcher;

/**

* Render the exception into an HTTP response.

*

* @param \Illuminate\Http\Request $request

* @return \Illuminate\Http\Response

*/

public function render($request)

{

return $this->run(new RespondWithJsonErrorJob(

status: 500,

message: $this->getMessage(),

));

}

}

Testing

When generating a job with lucid make:job a test class is automatically generated along, having markIncomplete() statement

in a stub method as a reminder to fill the missing test.

Their locations help us encapsulate our domains since they would contain all they need to operate in isolation.

lucid make:job UpdateProductDetails product

Would generate two files:

app/Domains/Product/Jobs/UpdateProductDetailsJobtests/Unit/Domains/Product/Jobs/UpdateProductDetailsJobTest

lucid make:job UpdateProductDetails product

Would generate two files:

app/Domains/Product/Jobs/UpdateProductDetailsJobtests/Unit/Domains/Product/Jobs/UpdateProductDetailsJobTest

The example below illustrates a simplified version of testing user input validation job:

namespace Tests\Unit\Domains\User\Jobs;

use Tests\TestCase;

use Lucid\Exceptions\InvalidInputException;

use App\Domains\User\Jobs\ValidateUserProfileInputJob;

class ValidateUserProfileInputJobTest extends TestCase

{

public function test_passes_validation()

{

$data = [

'name' => 'John Doe',

'email' => 'john@example.com',

'occupation' => 'Fun Seeker',

];

$job = new ValidateUserProfileInputJob($data);

$isValid = $job->handle();

$this->assertTrue($isValid);

}

public function test_fails_with_empty_name()

{

$this->expectException(InvalidInputException::class);

$this->expectExceptionMessage('The name field is required.');

$invalid = [

'name' => '',

'email' => 'john@example.com',

'occupation' => 'Fun Seeker',

];

$job = new ValidateUserProfileInputJob($invalid);

$job->handle();

}

}

Mocking

In most cases you wouldn’t want to mock with jobs because they are the actual units of work that need to be tested, though there would still be cases where you must mock. E.g. fetching content from an external source as illustrated in the example below, where we have a job to fetch articles from dev.to to test.

Our job looks like this:

namespace App\Domains\DevTo\Jobs;

use Lucid\Units\Job;

use App\Domains\DevTo\Client;

use Illuminate\Support\Collection;

class FetchDevToArticlesJob extends Job

{

public function handle(Client $devto): Collection

{

$articles = $devto->articles();

return collect($articles);

}

}

Client class code has been omitted, needless to say it is where the connection to dev.to happens to retrieve the articles:

Test

namespace Tests\Unit\Domains\DevTo\Jobs;

use Mockery;

use Tests\TestCase;

use App\Domains\DevTo\Client;

use Illuminate\Support\Collection;

use App\Domains\DevTo\Jobs\FetchDevToArticlesJob;

class FetchDevToArticlesJobTest extends TestCase

{

public function test_fetch_dev_to_articles_job()

{

$expected = json_encode([

'expected' => 'response',

'goes' => 'here',

], true);

// mock client

$mClient = Mockery::mock(Client::class);

$mClient->shouldReceive('articles')->withNoArgs()->andReturn($expected);

$job = new FetchDevToArticlesJob();

// execute job with injected mocked client

$articles = $job->handle($mClient);

$this->assertInstanceOf(Collection::class, $articles);

}

}